Use of Technology in Underserved Populations

This article is part of our coverage of the 2020 Association of Diabetes Care and Education Specialists virtual meeting, See our other articles related to the event, here.

Anne Peters, MD, is a professor of clinical medicine at the Keck School at USC, director of the USC Clinical Diabetes Programs and she works with Los Angeles County and on a diabetes program. She’s also a member of the Beyond Type 1 Leadership Council.

At the Association of Diabetes Care and Education Specialists (ADCES) virtual meeting, Dr. Peters presented a discussion called the “Use of Technology in Underserved Populations,” where she spoke about her work with vulnerable populations at the diabetes clinic she runs in East Los Angeles. At the clinic, there are disparities among people with pre-existing conditions, including those different types of diabetes, whose struggles are more evident during COVID-19.

Disparities in Diabetes Management

Dr. Peters has a lot of experience with disparities in diabetes management. She works in clinics that are located in areas with very different realities. She provides care to patients who have good health insurance coverage, a good income and easy access to technology in the western parts of Los Angeles, including Beverly Hills. In East Los Angeles, she cares for people with diabetes who may be uninsured or underinsured and live in areas particularly affected by poverty, barriers to technology and COVID-19.

“When we talk about disparities, we can talk about access in terms of economy, education, fewer skills to understand the terminology and especially cultural differences,” Dr. Peters said in her session.

During her talk, Dr. Peters emphasized the need to talk about cultural differences. “Many people do not want to accept advice from others who are of a different culture, but there are certainly ways in which we can work without generating greater distress than the one that comes from managing such a complex condition in environments and settings where life is already difficult,” she said during her presentation.

Barriers and Access to Diabetes Care

Barriers include access to healthcare and a system designed for other demographics. Peters’ patients in East Los Angeles are caregivers and field workers who require different pathways to accessing what they need when they need it. Many have complex lives and live in environments where they only receive care when they’re already very sick and many of them end up hospitalized, and even some die, because of this.

“It is easier for these populations to understand the information and relate to people from their own culture so some of the most obvious barriers include access to healthcare and technologies intended for other populations,” said Peters.

Dr. Peters mentioned that many of these people with diabetes already live with complications due to lack of access and seek simple solutions and not complicated answers. “I must help them by giving simple answers that don’t make their lives more difficult. My poorest patients already have complicated lives working three jobs, some have to travel to Mexico, and they cannot just put aside their jobs and lives to come to get medical attention,” she said.

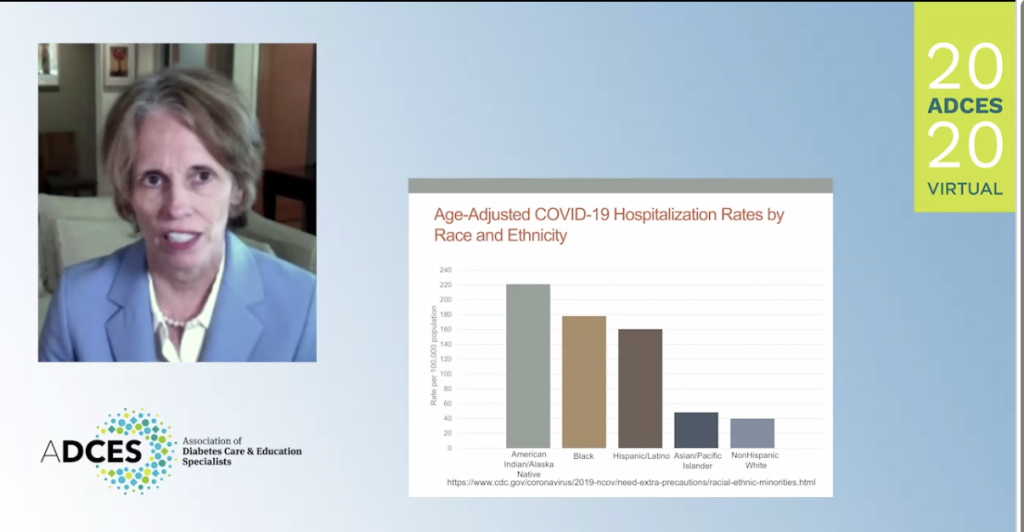

When talking about hospitalization during COVID-19, we see that the hospitalization rates are disproportionately higher precisely in the population Dr. Peters cares for in East Los Angeles.

The rates reported by other areas of California highlight the same problems observed in East Los Angeles.

Not all people are able to socially distance, they cannot always wear a mask and they are more exposed to the virus in addition to the fact that these families generally live in multi-family settings. Also, there are large groups of patients who have lost their jobs and therefore access to technologies such as cell phones, which makes telehealth difficult.

Additionally, some patients do not have email, so there are barriers on the websites, not only in terms of language but also in terms of understanding these sites and forms. The need for people who speak different languages to help patients who prefer to speak in their mother language is undeniable.

Adherence to Treatments

There is evidence of disparities and their impact on the ability to follow a treatment plan. Fewer patients have been able to adhere to and follow treatment. The patient’s culture, social assistance and family environment are non-modifiable factors that have an effect on this adherence. This is where healthcare providers can team up with social workers and therapists to help them work in this environment and see what can be done to improve their outcomes in relation to their circumstances. Modifiable factors also include support materials and the patient-provider relationship.

Technology in Underserved Populations

“Technology alone does not solve anything,” said Peters, who also emphasized that providing only the technology may not have the expected impact since it is necessary to work with patients gradually to make necessary changes.

“My solutions, no matter how well-intentioned, may not help,” she said.

Dr. Peters presented two cases from two of her East Los Angeles patients.

One of these cases is a man in his 40s with type 1 diabetes and a very high The 3-month average of one’s blood glucose levels. A1C who only checks his blood glucose a few times a week. So, she advised him to check his blood glucose more often and how this would improve his hemoglobin.

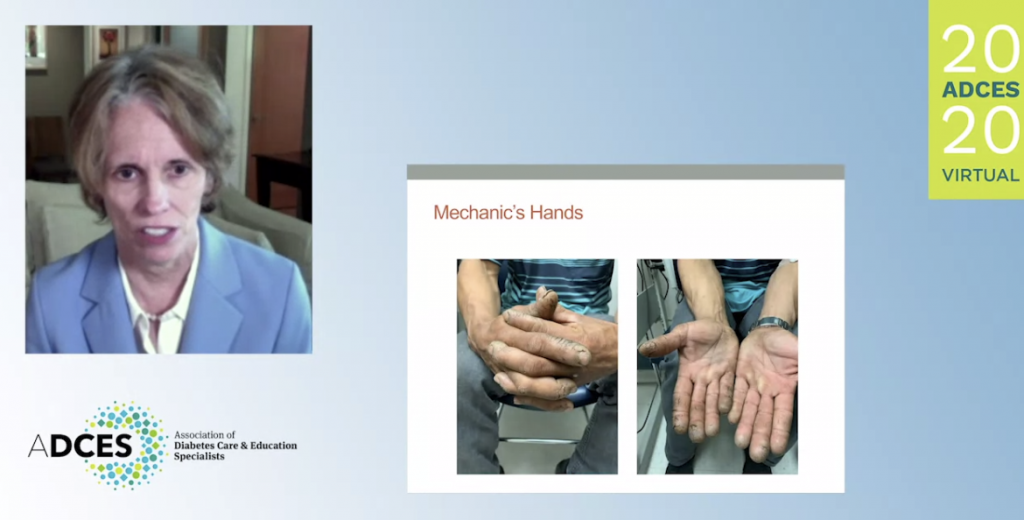

They asked her if she had seen his fingers.

Many of Dr. Peters’ patients use their hands to do heavy work in East Los Angeles, making blood glucose testing nearly impossible due to the calluses of their hands and fingers. Their circumstances make checking difficult, and without checking, diabetes management becomes more challenging.

The solution might have been to provide a A device that tracks blood glucose levels on an ongoing basis. continuous glucose monitor (CGM) to avoid finger sticks. However, this patient’s work involves moving between the vehicles that he fixes. Peters recommended he walk between the trucks, instead of sliding under them, to prevent tearing off the CGM since the combination of heat and sweat would detach the sensor. But this was not a viable solution because if he got up, his employer would see him and think that he wasn’t working hard enough.

In this case, it was the patient who found a solution. He came up with the idea of using a velcro belt to accommodate the sensor. These are the kind of problems that Dr. Anne and her team face in the eastern part of Los Angeles.

Why Diabetes Education Alone Isn’t the Answer, Either

Diabetes education, alone, won’t solve the disparities issue many of Dr. Peters’ patients face, either. Rather, there needs to be a comprehensive approach to it. Diabetes education should be included in a system where there is also support for them to use it to their advantage.

Dr. Peters’ team developed guides with multicultural texts and images to serve as guides for the soon-to-be-published STEP UP study, which are available to anyone who needs them to help these populations.

There is still a lot of work to be done especially with the Spanish-speaking populations, not only in Los Angeles but in many other states where there is a high percentage of people who speak Spanish. Including those who know these cultural differences, speak the language and have the desire to help our people may be a way of helping in the work that others do to help populations disproportionately impacted by diabetes and COVID-19.